On October 30, 2015, I took the newly completed electric train in Lima and after a short ride I left the chaos of the city behind and entered an oasis of peace, of the rest-in-peace kind that is. I could not think of a more appropriate place to visit on the eve of Halloween, than the Presbítero Maestro Cemetery Museum, a 2006 World Monuments Watch site.

As I climbed the cemetery’s museum staircase to enter the cemetery below, the grayness of Lima’s landscape became evident on a panoramic scale. From the dust on the rooftops of the burial blocks to the neblina (fog) obscuring the surrounding hills, everything in sight was panza de burro’s (donkey’s belly) color. The grass on the avenues however, provided a green contrast to the white architecture and gray sky—a luxury in a city where rain rarely falls.

The cemetery, which celebrated its 200th anniversary in 2008, is holding up relatively well after surviving several earthquakes, lack of maintenance, and pervasive air pollution. Matías Maestro, the cemetery’s creator, who in the 19th century established the neoclassical as the preferred style for religious architecture in Lima, would be pleased.

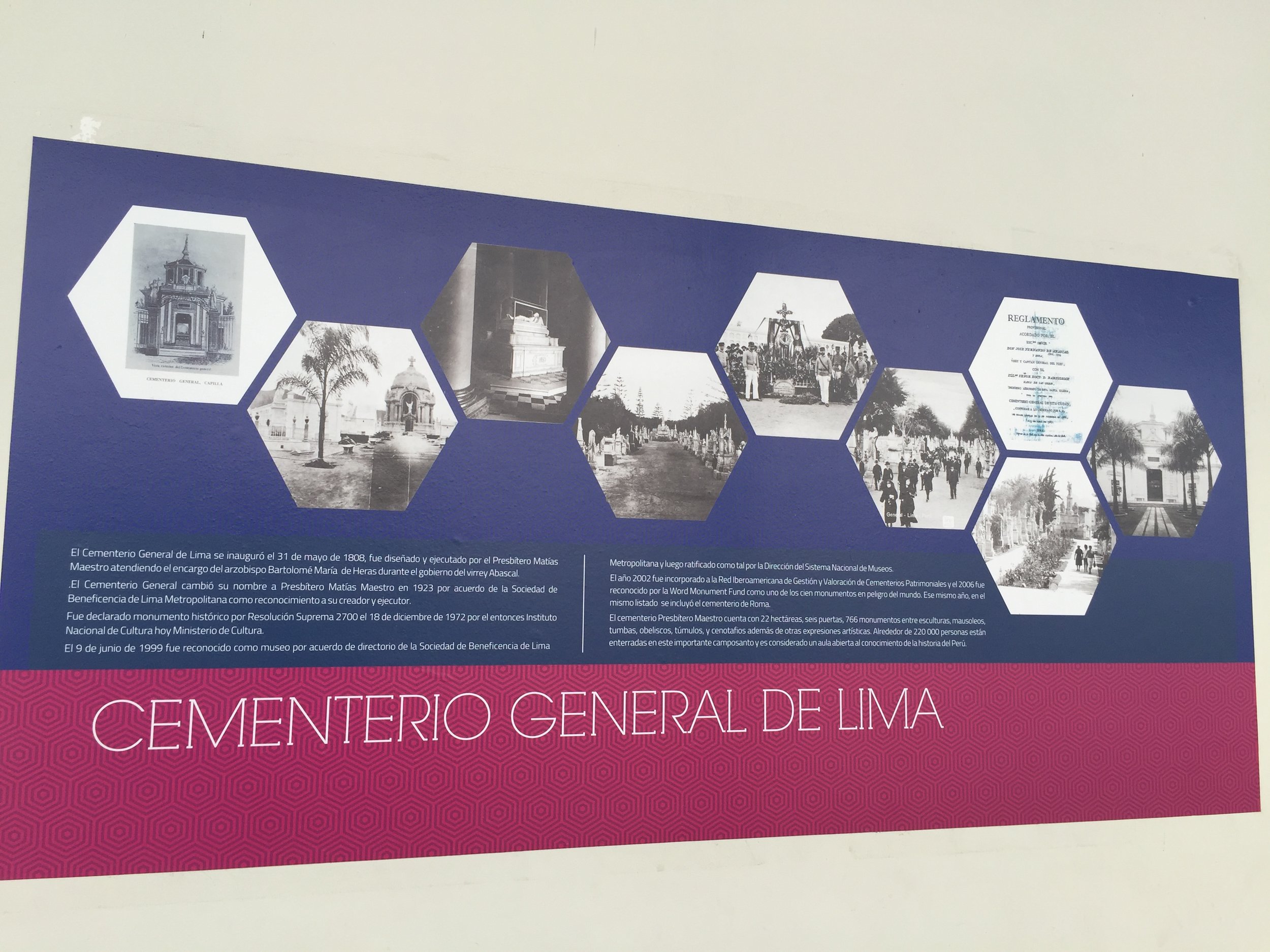

Near the museum entrance, an explanatory panel mentions proudly that the cemetery was included in the World Monuments Watch, together with a cemetery in Rome, the Cimitero Acattolico. Since its listing, the cemetery has come a long way. The electric train now has a “Presbítero Maestro” station which makes the cemetery easily accessible by public transportation. The museum collection includes two restored hearses, which sit outside, as reminders of an earlier way of life (and death) in Lima, as well as other funerary objects.

At the time of my visit, the cemetery was the main protagonist of the XVI Iberoamerican Meeting on the Valorization and Management of Heritage Cemeteries. The symposium focused on research related to cemeteries from Argentina to Venezuela, and included a stone conservation workshop and site visits around Lima. While I waited to meet one of the meeting organizers, I saw the resting places of important people buried there such as Presbítero Maestro himself, Mariscal Castilla, and composer Felipe Pinglo, as well as mausoleums belonging to old families such as the Osma, Miro Quesada, Diez Canseco, and others whose names appear on many of the streets of Lima. Their marble and granite mausoleums feature eclectic, neo-gothic, neo-classic, art nouveau and modern details, and many hold statues sculpted by Italian artists.

One structure that caught my attention as I strolled around the cemetery was Marcela Perez de Cuellar's mausoleum, a relatively small house-like structure of gray marble with just her first name above its entrance. Seeing her resting place brought back memories of the time a few years ago when I had the honor of collaborating with her in her role as the first president of WMF Peru. She was elegant, energetic, and passionate, and a consummate diplomat. As I walked away towards the cemetery’s exit on this gray October morning, I felt a pang of nostalgia for those bygone years, but also an inspiration to work hard to continue her mission of preserving the cultural heritage of Peru.

My appointment never showed up, but it was a fruitful morning after all.